The Dassanech People : Omo Valley, Ethiopia

I spent over ten years visiting the Omo Valley, a place where time seemed to flow as slowly as the river that cut through its heart. Between 2010 and 2015, I worked on a documentary about the region, capturing the culture and lives of the people in a place National Geographic once called “the last frontier in Africa.” Before that, I had come to the Omo to photograph and explore. It was a land where communities lived so close to the rhythms of nature, both good and bad, where every shift in the landscape echoed through their lives.

I camped along the banks of the Omo River, beneath towering trees that offered shade and a cooling breeze. The river itself, at times calm, at other times fiercely rushing, flowed past me, heading toward the Delta and Lake Turkana, the largest desert lake in the world. The land here, though beautiful and stark in its simplicity, was alive with the pulse of nature. But as the years passed, I saw that life in this valley—so tightly connected to the river’s rhythm—was changing. Foreign agricultural projects, driven by forces beyond the valley’s control, were slowly creeping in, while the land itself had grown increasingly fragile due to overgrazing.

In 2006, I made my first trip to the Omo. I arrived during a time of devastation—flooding had ravaged the land just north of Lake Turkana, where the Dassanach people lived. The river was swollen, the water’s power overwhelming. We took our boat south from camp, heading toward the Delta. Along the way, I saw villages and islands, their outlines blurred in the mist. Giant herons swooped overhead, their wings beating in the heavy air. Crocodiles lay in the sun, motionless on the banks. Occasionally, monkeys swung between the trees, calling out as if to welcome us. The sight was serene, but beneath it, there was a quiet unease. The land, though beautiful, was scarred by the floods—villages displaced, crops drowned, and lives disrupted.

Our boat was 30 feet long, powered by a 175-horsepower motor. It was a vessel built for strength, the perfect tool to navigate the powerful currents of the Omo River. The cover shielded us from the harsh African sun, allowing us to travel deeper into the valley, to places where few outsiders had ever ventured. Every day, the river demanded respect. It was never about drifting; it was about controlling the boat, using strength and skill to keep us moving forward, to places where few had ever set foot.

Steve McCurry, a photographer and friend known for his iconic Afghan Girl image, often joined me on my trips. We had spent time together in far-off places—India, Burma, and Africa. We both shared the same instinct: to capture moments that revealed deeper truths about people, place, and time. When Steve came to the Omo, we’d spend our days on the boat, moving from village to village. The river was our guide, and the people were our subjects.

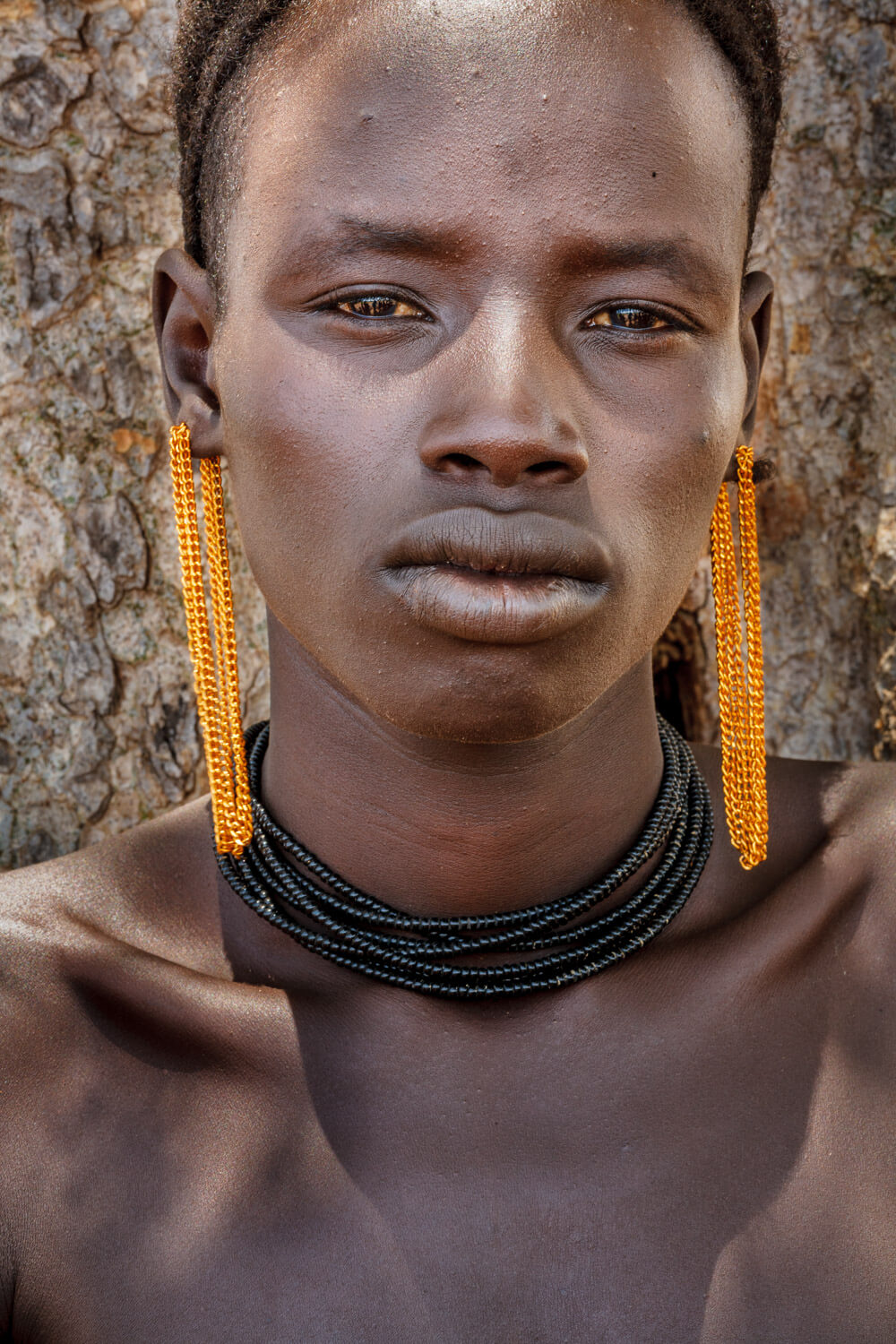

Steve had a gift—he could connect with people in a way few others could. His kindness shone through his eyes, and his humor was evident in his smile. It was through this connection that doors opened, and we were invited into lives that had known little of the outside world. Steve would spend hours with his subjects, waiting for the perfect moment when the light, the expression, and the background came together. It wasn’t just about taking photographs—it was about capturing the soul of the moment.

One of the most profound experiences Steve and I shared in the Omo was during the Dimi Ceremony, a sacred event where young men are initiated into manhood. It happens only once every four years, a rare and sacred ritual. We were lucky to be invited.

The energy in the village was electric, the air vibrating with anticipation. The chanting started softly, then grew louder, more rhythmic, more hypnotic. It was as if the voices of the men and women were part of the very pulse of the land itself. The dancers moved in a trance-like rhythm, their bodies moving in unison, their voices rising in a chant that echoed the traditions of their ancestors. The elders, cloaked in leopard skins, stood with quiet dignity, their presence commanding respect. As I watched, I realized that this was not just a ceremony—it was a testament to a culture fighting to maintain its identity in a world that was rapidly changing.

But even in this sacred moment, I felt the change in the air. The valley, the river, and its people were not immune to the forces reshaping the world. Several dams had been built upstream, and the Omo River, once so mighty, was no longer as powerful. The reduced flow of water had impacted agriculture, and Lake Turkana, once rich in life, was becoming increasingly saline. The lake that had sustained entire communities for centuries was slowly losing its life-giving qualities, and the people who relied on it for fish and water were watching their world slip away.

The Dassanach, in particular, were facing more than just environmental challenges. The dams, the shrinking river, and the encroachment of neighboring tribes like the Turkana and the Nyangatom, who often raided their cattle, had pushed them into a struggle for survival. The hardship was no longer just from the unpredictable whims of nature—it was the result of a world outside the valley, a world that didn’t understand or care about the fragile balance of life in the Omo.

After more than ten years of visiting the Omo Valley, forming deep bonds with its people, and witnessing the hardships brought on by both nature and outside forces, I knew it was time to leave. It wasn’t just the environmental shifts—it was now man-made damage, bushland destroyed, the rising salinity of the lake, the difficult human conditions—it was a feeling that I had witnessed everything I could and perhaps more than I should. The Omo, once timeless, was changing before my eyes, and I realized that I had reached the end of my time there.

Leaving wasn’t easy. The Omo had become a part of me, its rhythms woven into my own. It wasn’t just a river I had come to know—it was a way of life, a culture, a connection to something deeper. But sometimes, you have to step away in order to carry what you’ve learned.

And so, after one last journey down the river, photographing the land and its people, I packed my bags and left the Omo Valley. But the faces, the stories, and the beauty—those, I carry with me, always. The memory of the Omo, its people, and the river that defined it, will remain with me, a reminder of a place that is slowly slipping away.