Vietnam

I grew up in the 1950s and 60s, came of age during the Vietnam War and eventually joined the Navy Reserve. It was there, at the Navy School of Photography in Pensacola, Florida, that my journey as a photographer began. The war cast a long shadow over those years. Friends were lost, and Vietnam became, for many of us, a place defined by conflict and sorrow, a place of ghosts.

So when I first traveled to Vietnam, decades later, I wasn’t sure what to expect. Hanoi was my entry point. I was struck not by remnants of war, but by a city that was modern, bustling, and, in some ways, more dynamic than cities back home. Yet the past was never too far away. Now and then I’d see a war memorial, or the rusted carcass of an old tank hidden among the trees. These glimpses would bring back memories of those turbulent years and the friends who never came home.

Hanoi also awakened my senses in other ways. The food, especially the pho from street stalls, was fresh, fragrant, and addictive. I’d sit on a low stool under the buzz of neon lights, slurping noodles, surrounded by locals. It was here that I began to feel the real Vietnam, not the one from the newsreels or old photographs, but a living, changing country.

Yet my true destination lay further north. I was drawn to the highlands near the border with China and Laos, where the Hmong and other ethnic groups live in small, remote villages. The journey was long and often difficult. Sometimes the roads were little more than muddy paths carved into mountainsides. Rain would turn the red earth slick, and our progress would slow to a crawl. But these obstacles only made the arrival more meaningful.

The landscape was stunning, terraced fields carved like steps into the hills, bamboo groves rustling in the wind and mist curling through valleys like smoke. In these villages, I found what I had come looking for, people living in close connection with their land and traditions. I spent weeks at a time with the Hmong, getting to know their daily and way of life.

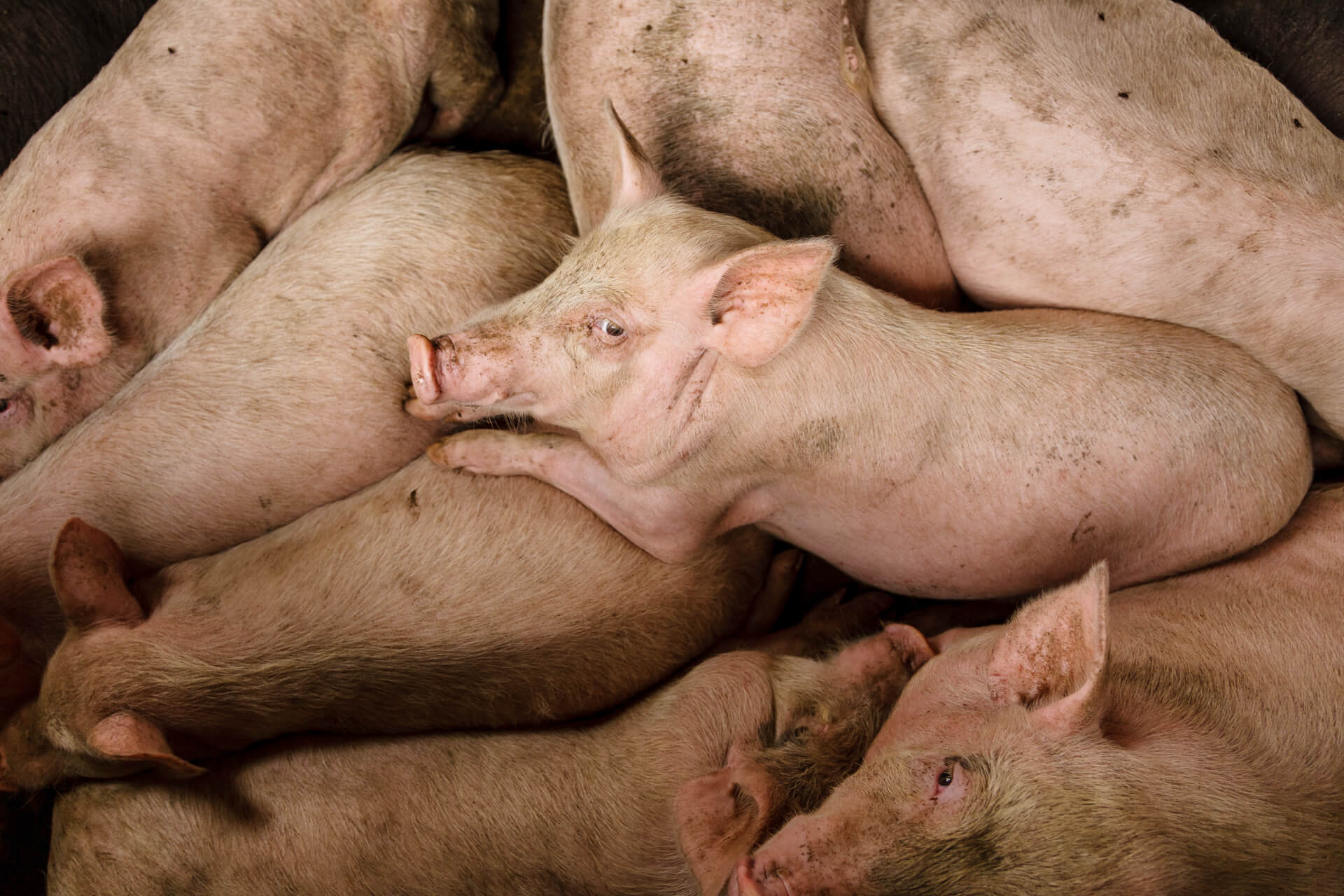

Most of the Hmong I met were agriculturalists, farmers and their families, working steep fields with hand tools, raising pigs and chickens, living a communal, subsistence life with grace and resilience. In the afternoons, I would often sit on the porch of a wooden house, watching women weave textiles on large looms. The fabrics were stunning, each color, each pattern specific to their clan, their village, their story.

The Flower Hmong wore garments exploding with color, bright pinks, greens, and oranges layered in intricate embroidery. Their clothes were like living gardens. The Black Hmong, by contrast, favored deep indigo, dyed using traditional batik methods. Women painted beeswax onto the cloth in complex patterns before immersing it in dye. The designs, spirals, stars, seeds, carried symbolic meaning. And the Red Dao, not Hmong but their neighbors, wore crimson headscarves adorned with coins and tassels, and shaved their eyebrows as part of their spiritual tradition.

One detail I’ll never forget: some of the older Hmong women applied a heated black tar to their teeth, a traditional practice that turned them a shiny obsidian. It was once considered beautiful, and a sign of maturity and health. Watching them laugh, black teeth flashing, I was reminded that beauty is always culturally defined.

These textiles weren’t just clothing. They were identity. They told others who you were, where you were from, and what you believed. They were worn in life and prepared for death. In Hmong belief, the spirit needs to be dressed properly to find its way home.

The Hmong are a people with a long and complex history. Originally from the Yellow River region of China, they were pushed south over centuries by war and oppression. Many settled in the highlands of Vietnam in the 18th and 19th centuries. Today, they are among Vietnam’s largest ethnic minority groups, living in rugged provinces like Hà Giang, Lào Cai, and Lai Châu.

They have their own languages, customs, and social structures centered around clans and spiritual practices. Shamans still play an important role, acting as healers and mediators between the human and spirit worlds. Marriage is arranged through clan negotiation, and rituals mark every stage of life.

But modern pressures are changing things. Tourism brings income but also poses risks of cultural dilution. Factory-made clothes and the lure of urban life threaten to replace old traditions. Even so, many young people still wear traditional dress, especially for festivals or market days. There is a pride in heritage that endures.

My time in the highlands left a deep mark. Sitting with families, eating with them, listening to their stories, even without always sharing a language I felt a connection that transcended borders and histories. It reminded me that behind every cultural artifact, every embroidered stitch, there is a human story, one of endurance, memory, and quiet beauty.

Vietnam is no longer the Vietnam of my youth. It’s a place that contains many truths: of sorrow, survival, and vibrant life. The journey north took me further than I expected, not just across miles, but through time, through memory, and into something new and different.